Behind the Dictionary

Lexicographers Talk About Language

A Birthday Card for Dr. Johnson

Today, September 18th, is Samuel Johnson's 300th birthday. The English essayist, poet, novelist, and witty conversationalist whom we know mostly through the anecdotes recorded by his friend and biographer, James Boswell, and his other friends, became famous in his day for his two-volume Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1755. Dennis Baron, professor of English and linguistics at the University of Illinois, wishes Dr. Johnson a happy birthday — and a happy birthnight.

It may have been Noah Webster, who was half a century younger, whose name would become synonymous with dictionary, but no lexicographer rivaled Samuel Johnson in turning out elegant, opaque, intricate, and occasionally witty definitions for words both familiar and obscure.

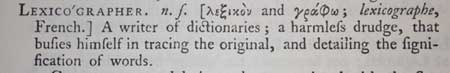

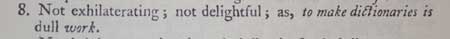

Johnson defined lexicographer as "a harmless drudge" (s.v.) and dictionary-making as "dull work" (s.v. dull, sense 8), but he surely enjoyed cranking out definitions for odd words like dandiprat, "an urchin," fopdoodle, "a fool," giglet, "a wanton," and jobbernowl, "a block head."

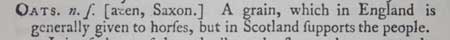

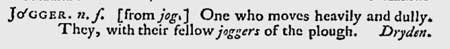

Besides the occasional definitional joke, like Johnson's often-repeated definition of oats, we also find in his dictionary words whose meaning has changed: fireman, "a man of violent passions," pedant, "a schoolmaster," and jogger, which Johnson characterizes as movement that is far from aerobic, and he liberally illustrates his definitions with citations from well-known literary and scientific sources:

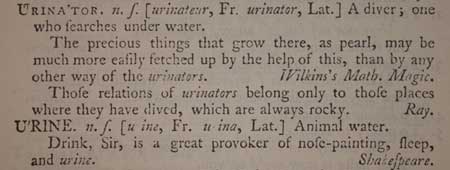

Urinator, for Johnson, is "a diver," while urine, "animal water," hasn't changed all that much.

There are "low words," like bum and fun:

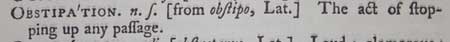

There are plenty of strange words, like obstipation:

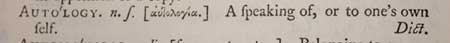

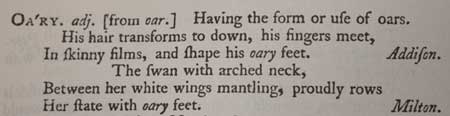

not to mention autology, a kind of neoclassical ego trip, and oary, used by major authors to describe the oversized neoclassical foot:

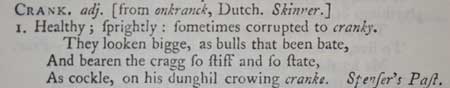

Johnson's definition of crank (he says it's sometimes corrupted to cranky) as "healthy; sprightly," seems the opposite of what it means today:

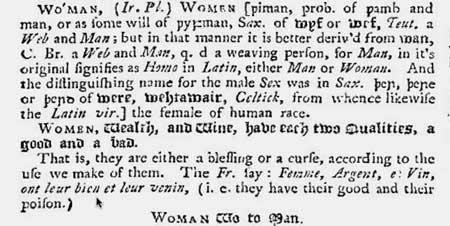

Johnson's dictionary contains mistakes, both subtle and blatant. He traces peacock back to an original "peak cock, from the tuft of feathers on its head." In fact, the word is based on the Old English bird name pea, from the Latin pava. But 18th-century derivations are often wrong. A popular set of etymologies that Johnson does not copy derives woman from womb-man, web-man, or woe to man:

Nathan Bailey, in his Dictionarium Britannicum (1736), derives woman from

web + man, 'a weaving person,' and mentions the popular etymology 'woe to man.'

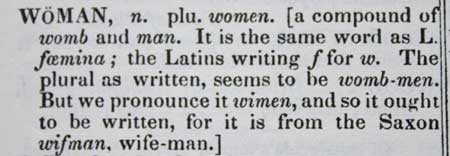

The word woman comes from the Old English wifman, which literally means 'female person.'

A corresponding form, *werman, 'male person,' which does not occur in the Old English

database, would be the masculine equivalent (however, we do find examples of wer and

werwulf). But in his 1828 Dictionary, Noah Webster, whose family name derives from a word

meaning 'woman weaver' (-ster is a feminine suffix in Old English; the masculine equivalent

of webster would be webber — compare spinner, spinster) buys into a popular but incorrect

etymology tracing woman to womb + man, an etymology that Johnson did not credit.

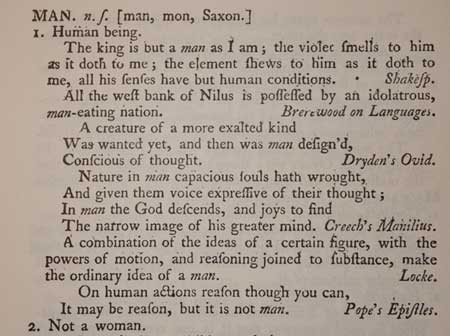

But while he doesn't repeat the "woe to man" canard, Johnson is certainly no feminist. He gives the primary meaning of man as "human being," but also adds the definitional caveat, "not a woman":

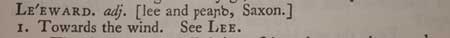

Some of Dr. Johnson's definitions are wrong. He treats windward and leeward as synonyms, when in fact they are opposites (he also classifies leeward as an adjective, windward, an adverb):

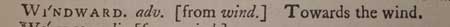

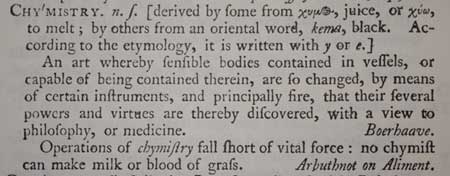

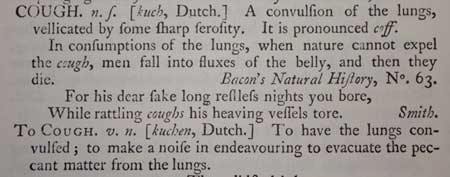

But some of the definitions are just more opaque or infathomable than the words they define:

chymistry:

cough:

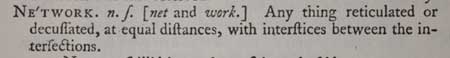

network:

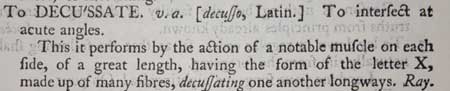

decussate:

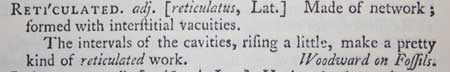

reticulated:

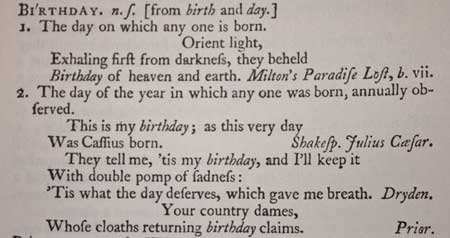

It's fitting to end this digital birthday tribute to Dr. Johnson with his own matter-of-fact definition of birthday, "the day on which any one is born,"

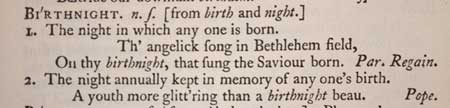

together with his definition of the much less common word, birthnight:

So let me join all of Dr. Johnson's fans in wishing the outspoken English lexicographer — if Johnson were alive today, Boswell would be recording his pithy gripes and witticisms in tweets — a happy birthday, and a happy birthnight. And here's my birthnight card for Dr. J:

A Hollywood ending for a latter-day Dr. Johnson: in "Ball of Fire," a seldom-seen 1941

movie directed by Howard Hawks, with screenplay by Billy Wilder, Gary Cooper stars as an

ivory-tower lexicographer working on slang who realizes that he needs to hear how real

people talk, and ends up helping a beautiful singer (Barbara Stanwyck) escape from the mob.