Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

The Clean and the Unclean

"And the leper in whom the plague is, his clothes shall be rent, and his head bare, and he shall put a covering upon his upper lip, and shall cry, 'Unclean, unclean.'"

—Leviticus 13:45, King James Version"Make no mistake, if they send us a [bill] that is unclean, they are virtually shutting down the government."

—Senator Charles Schumer (late September, 2013)

The distance between the Biblical use of unclean and the meanings that might be inferred from Senator Charles Schumer's use of it is surely very great — chronologically, and, one would hope, semantically. But it was an unusual choice of words from the Senator, an articulate and intelligent speaker. He could have used any number of non-negated adjectives to characterize what he expected might issue from the House of Representatives, he could have said "not clean," or he could even have simply said "an unclean bill," rather than showcasing the adjective at the end of the clause. What associations reverberate from his use of unclean to characterize the budget legislation that he thought might be returned to the Senate from the House?

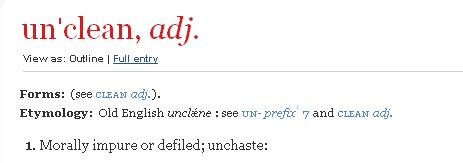

As un- words go, unclean is marked in a number of ways. First of all, by being extremely ancient, being present in Old English in nearly identical form. Here's a screenshot of the beginning of the OED entry for the adjective.

Second, unclean, from its debut in English, is a word freighted with far more associations that you would expect from a word that simply negates an extremely common and frequent adjective. Third, unclean is, despite its ancient pedigree, infrequent in English today, a fact this is surely connected with the second point: unclean is so laden with connotations of moral turpitude and disease that it's problematic to use it if you intend no more than a relatively judgment-free idea of "not clean." Unclean is used today overwhelmingly in writing on religion — an unsurprising fact when you take into account that unclean appears nearly 200 times in many standard Bible translations. Its most frequent collocation is "unclean spirit," another Biblical term with several mainly New Testament appearances. In Old Testament usage, the distinction between clean and unclean is frequently in reference to detriments from ritual purity. Leviticus has numerous references to uncleanliness as it pertains to animals and food, disease, and bodily discharges, all of which present impediments to those who would stand in the presence of God.

All-purpose negating words, particles or affixes are a common and handy feature of languages generally so perhaps it's worth asking: when is adjectival negation via un- an act that requires exegesis because the speaker or writer is motivated by something more than convenience? In most cases it may be impossible to know: words do, most of the time, simply pour out of us and we may be at a loss to explain their provenance. But a statistical approach may shed some light on factors that influence the choice of a negated adjective in place of one that carries a similar meaning without the presence of a negating morpheme.

The headline adjectives in English — those with extremely high frequencies (in the top 200 of English word frequencies overall) are rarely negated with un-. Most of them, such as new, good, large, or high, have an all-purpose antonym that is the best choice to convey the opposite meaning. This is, again, a feature typical of languages generally, and perhaps especially characteristic of English, a language that is synonym-rich in adjectives — we often have a choice of a Latinate or Germanic derivative, with or without differences in nuance. The three most frequent un- adjectives in English are unable, unlikely, and unusual, and even they are all less frequent than their unprefixed opposites.

A handy tool that modern corpus linguistics has made available is the distributional thesaurus. A traditional thesaurus, somewhat like the Visual Thesaurus, catalogs words that share an element of meaning. A distributional thesaurus takes a strictly statistical approach. It tells you, for a given word, what other words in the language, surveyed across a corpus, behave in about the same way — which is to say, team up with the same words in the same syntactic slots across hundreds or thousands of sentences. As an example: words that are distributionally similar to the adjective unusual are, in descending order, strange, extraordinary, unique, interesting, odd, distinctive. As you can see, none of these words is a negated adjective, and they are all, perhaps aside from interesting, acceptable traditional synonyms of unusual. By contrast, words that are distributionally similar to unclean are, again in descending order, impure, filthy, immoral, polluted, unworthy, unsanitary. This list is interesting for two reasons: the preponderance of other negated adjectives, and the presence of other adjectives that carry a strong connotation of undesirability and moral opprobrium.

In their monumental study called Metaphors We Live By, authors George Lakoff and Mark Johnson remark (in the afterword to the book, newly written for the current edition), that

Our basic understanding of morality arises via conceptual metaphor. There is a system of approximately two dozen metaphors that arise spontaneously out of common, everyday experience in cultures around the world. Since morality is concerned with well-being, whether one's own or that of another, fundamental experiences concerning well-being give rise to conceptual metaphors for morality. People are better off in general if they are strong not weak; if they can stand upright rather than having to crawl; if they eat pure, not rotten, food; and so on. These correlations give rise to metaphors of morality as strength and immorality as weakness, morality as uprightness and immorality as being low, morality as purity and immorality as rot, and so on.

What, then, was Senator Schumer really suggesting when he warned about the unacceptability of a "bill that was unclean" being passed to the Senate? Whether intentionally or not, he used a word that resonated at a much deeper level than might seem warranted by the circumstances. The Senator gets credit for a brilliant rhetorical flourish. Whether it resulted in a bill that was "unclean" is still being debated today.