Word Count

Writers Talk About Writing

Ctrl+Shift+Return: Keys to Your Computer

Your computer's keyboard has around 110 keys by which you can make your wishes known to the machine. Most of these have obvious labels: if you press the A key, the letter A appears on the screen. Some are less obvious, though — the Shift key and the mysterious Ctrl key — and in this article I'll explore why they're named what they're named.

Long before computers, many practical issues about using a machine to write had already been worked out for the typewriter. If you've never used a typewriter, you might be interested in this video that shows one in action.

In a typewriter, the paper is rolled around a platen that's part of a carriage that can move right and left. Letters are cut onto slender pieces of metal called typebars. Pressing a key on the keyboard causes the corresponding typebar to hit the paper through an inked ribbon. After the typebar hits the paper, the carriage moves to the left by one letter.

Early on, people learned to cut two letters on a single typebar. When you press a key, the lower letter strikes the paper. But you can also press a key to raise — or shift — the carriage, which causes the upper letter on the typebar to hit the paper instead. Thus the Shift key was born. (In the video, you can see the carriage being shifted for the very first letter that's typed, at 00:12.)

Typebars [Source]

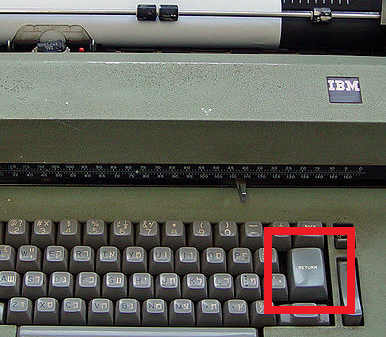

When the typist reaches the end of a line, he or she uses a lever to return the carriage to the left and advance (feed) the paper up one line (00:29 in the video). When manual typewriters were eventually electrified, this somewhat laborious action was reduced to a single keystroke: the Return key.

Return key on IBM Selectric typewriter [Source]

While the typewriter was becoming a ubiquitous office tool, inventive minds in the communications industry were developing the teletypewriter (branded as Teletype, which became a generic term for it) as an improvement on the telegraph for sending electronic messages. With Teletypes, an operator far away could type a message and then send it. On the receiving end, another Teletype machine would come to life and clatter away, typing out the message.

To send signals over a wire, the Teletype machine represented each character as a numeric value. A standard set of codes developed (the ASCII chart), where 32 is a space, 46 is a period (.), 65 is the letter A, 97 is the letter a, and so on. Here's a chart of those values. (I realize that looking at charts is stultifying, but bear with me; it will become more interesting in a few moments.)

| 0 | NUL | 32 | (space) | 64 | @ | 96 | ` |

| 1 | SOH | 33 | ! | 65 | A | 97 | a |

| 2 | STX | 34 | " | 66 | B | 98 | b |

| 3 | ETX | 35 | # | 67 | C | 99 | c |

| 4 | EOT | 36 | $ | 68 | D | 100 | d |

| 5 | ENQ | 37 | % | 69 | E | 101 | e |

| 6 | ACK | 38 | & | 70 | F | 102 | f |

| 7 | BEL | 39 | ' | 71 | G | 103 | g |

| 8 | BS | 40 | ( | 72 | H | 104 | h |

| 9 | HT | 41 | ) | 73 | I | 105 | i |

| 10 | LF | 42 | * | 74 | J | 106 | j |

| 11 | VT | 43 | + | 75 | K | 107 | k |

| 12 | FF | 44 | , | 76 | L | 108 | l |

| 13 | CR | 45 | - | 77 | M | 109 | m |

| 14 | SO | 46 | . | 78 | N | 110 | n |

| 15 | SI | 47 | / | 79 | O | 111 | o |

| 16 | DLE | 48 | 0 | 80 | P | 112 | P |

| 17 | DC1 | 49 | 1 | 81 | Q | 113 | Q |

| 18 | DC2 | 50 | 2 | 82 | R | 114 | R |

| 19 | DC3 | 51 | 3 | 83 | S | 115 | S |

| 20 | DC4 | 52 | 4 | 84 | T | 116 | T |

| 21 | NAK | 53 | 5 | 85 | U | 117 | U |

| 22 | SYN | 54 | 6 | 86 | V | 118 | V |

| 23 | ETB | 55 | 7 | 87 | W | 119 | W |

| 24 | CAN | 56 | 8 | 88 | X | 120 | X |

| 25 | EM | 57 | 9 | 89 | Y | 121 | Y |

| 26 | SUB | 58 | : | 90 | Z | 122 | Z |

| 27 | ESC | 59 | ; | 91 | [ | 123 | { |

| 28 | FS | 60 | < | 92 | \ | 124 | | |

| 29 | GS | 61 | = | 93 | ] | 125 | } |

| 30 | RS | 62 | > | 94 | ^ | 126 | ~ |

| 31 | US | 63 | ? | 95 | _ | 127 |

Most of the characters in the chart are ones you'd find on a typewriter. But the first 32 characters are cryptic, like BEL, HT, LF, and CR. These are known as control characters — signals that could be sent to the Teletype machine not for display, but to control how it operates. For example, STX (2) is the "start of text" character; HT (9) is "horizontal tab"; CR (13) is "carriage return"; LF (11) is "line feed"; and BEL (7) is "bell" — that is, ring the bell. When an operator originally typed the message, he or she would get to the end of a line and press a return key, just like with a typewriter. This embedded a CR character (carriage return) and a LF character (linefeed) into the message at that point. When the message was received by another Teletype machine and printed out, the control characters embedded in the message told the machine when to return the carriage and feed a new line. The message might also include other control characters for functions like inserting a tab, starting a new page (FF or form feed), and so on.

Back to our naming story. Early Teletype keyboards were comparatively primitive (they included only uppercase letters), so they included a Ctrl key that let the operator embed control characters into a message.

Teletype keyboard [Source]

The way it worked was clever: if the operator held down the Ctrl key while typing a character, the Teletype machine in effect subtracted 64 from the value of that letter. Glance again at the chart from earlier. Let's say that the operator wanted a horizontal tab (9). The operator could press Ctrl and I (73) at the same time. To create a page break/form feed (12), the operator pressed Ctrl+L. To embed a character to ring the bell, the operator used Ctrl+G.

Early Teletype machines didn't even have lowercase letters, but when those were added, the machines used a similar technique to let users specify uppercase letters — that is, to encode the action of the Shift key. Holding down the Shift key while typing a letter subtracted 32 from the value. If you look at the ASCII chart, you'll see that the values of uppercase and lowercase letters differ by 32, so that a (97) becomes A (65). (This explanation is simplified somewhat, I should note.)

When computers were developed, it was natural to adapt the encoding scheme and the keyboard of Teletype machines for input and output. Teletype machines quickly gave way to terminals, and along the way, the Return key became the Enter key, because it no longer had much to do with returning the carriage and instead was about entering (sending) a command for the computer.

These days, of course, we no longer need to encode control characters by hand. (Although we do still use the Shift key for its original purpose of creating capital letters, albeit no longer by physically shifting a carriage.) Most programs that you use on your computer have more interesting uses for the Ctrl key than ringing the bell or embedding a tab. For example, Ctrl+i, which would produce ASCII value 9 (for the tab), is used in many Windows programs to format text using italics.

But deep under the covers, you can still find traces of the old Teletype machines. If you have a Windows computer, open Notepad and try entering some control codes — for example, press Ctrl+Shift+m to insert a carriage return, and Ctrl+Shift+i to insert a tab. And don't forget to press Ctrl+Shift+g to produce a beep, which is the modern equivalent of the typewriter's old bell.

If you can actually put your hands on an old typewriter or Teletype machine, they feel like fossils from an earlier age. Still, it's pleasing to me that when you tap away at your keyboard (even a virtual keyboard on a tablet computer), there's still a direct line, both technically and etymologically, between those keys and machines of the pre-computer era.