Word Routes

Exploring the pathways of our lexicon

How the King Overcame His Stutter

This weekend, the movie "The King's Speech" gets its nationwide release in the United States, and it's already getting talked about as a front-runner for the Oscars. It has also received a great deal of buzz in the speech therapy community for its sensitive and credible depiction of King George VI's speech impediment and the methods that his therapist Lionel Logue used to overcome it. I take a look at the movie and the real-life story in my latest On Language column, appearing in the Oscars issue of the New York Times Magazine.

For the column, I got to interview the screenwriter, David Seidler, who drew from his own experiences growing up with a stutter to inform the movie's portrayal of "Bertie" (a.k.a., Prince Albert Duke of York, the man who precipitously ascended to the British throne after the abdication of his brother Edward). I also spoke to Colin Firth, whose moving performance in the role of Bertie could very well garner him his first Academy Award for Best Actor. Geoffrey Rush as Lionel Logue also does a marvelous job as the unconventional speech therapist who breaks down Bertie's inhibitions using such vocal techniques as tongue twisters.

Firth and Rush enlivened Seidler's screenplay by consulting some newly discovered primary documents about the relationship of Bertie and Logue. A large amount of Logue's diaries, correspondence and other materials had been gathering dust in the attics of his descendants until recently. His grandson, Mark Logue, has drawn on this material for a book published in conjunction with the movie by Sterling Publishing Co., also called The King's Speech.

One such document, reproduced on the Times website accompanying the On Language column, shows the draft of George VI's famous 1939 "eve of war" speech, annotated in Logue's hand with lines marking pauses and occasional words substituted to avoid problematic sounds. For instance, the speech (reportedly drafted by Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty) originally had the sentence, "Over and over again, we have tried to find a peaceful way out of the differences between my Government and those who are now our enemies." Logue scratched out "my Government" and replaced the words with "ourselves," likely to avoid the "g" sound at the beginning of "Government." The King often stumbled on words starting with /g/ and /k/ (sounds that phoneticians call "velar plosives").

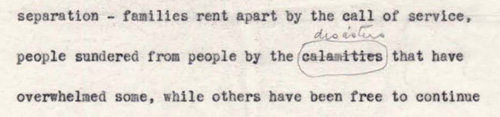

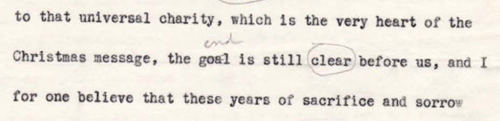

Here are examples of Logue's word substitutions from a later radio address, given by George VI on Christmas 1944:

In this draft (courtesy of the Logue Archive), you can see Logue has replaced calamities with disasters and goal with end, again focusing on those initial velar plosives. This type of word substitution is no longer a common practice among speech therapists, according to those I consulted for the column — instead, therapists might work on breaking the word down into constituent syllables to overcome difficulties with particular phonemes. But Logue's techniques seem to have been effective with his royal patient Bertie, likely because they helped instill a relationship of trust and familiarity that helped the King relax and concentrate on his public speaking. As I note in the column, Bertie was never "cured" of his stutter, but the way that Logue built rapport with him made all the difference.