Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

2019: The International Year of Indigenous Languages

Unesco, the United Nations agency, chooses a cultural theme to highlight and celebrate every year. Now, in 2019, indigenous languages are ready for a long overdue closeup. What's that got to do with me? you may ask. Read on to find out.

The term indigenous language might seem at first glance to include all languages, because all natural languages were indigenous somewhere, at some time—that is to say, spoken in the place where they originated. While this is still true of many languages today, indigenous language specifically designates a language spoken by a linguistic community (often a minority) that has settled in an area for generations. Many indigenous languages face an uncertain future: as native speakers age and younger speakers are more drawn to majority languages that offer what are perceived as social or economic benefits, indigenous languages face extinction.

Most readers will know that this is not a new story. Many hundreds of languages in the world are known today to be extinct, with languages of North and South America probably outnumbering those other places in the world. And surely, many hundreds of other languages disappeared before writing systems were well developed and so died their natural death in obscurity. So on the one hand, it might be argued that language extinction is a natural process that will happen regardless of efforts to stop it. On the other hand, just as the loss of biodiversity is a threat to our well-being, the loss of linguistic diversity also diminishes the quality of human life. It's therefore worth doing what we can to promote the vitality of threatened indigenous languages, and 2019 is the year to boost that effort.

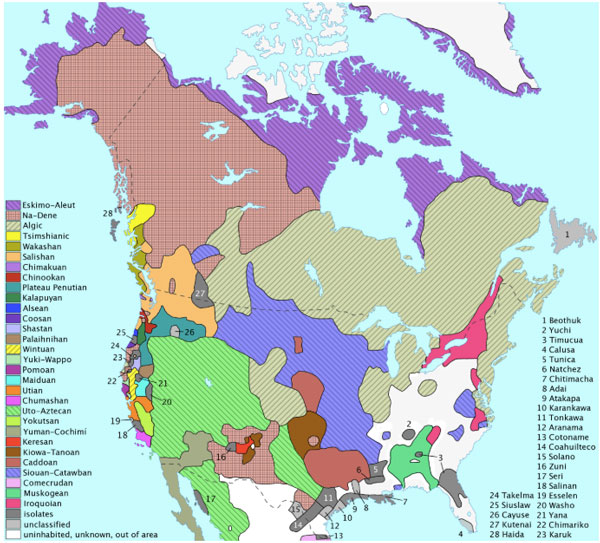

Nearly ten years ago, Ben Zimmer wrote about the situation of English in the Philippines and the ways that both English and Spanish had made headway in the island nation, often to the detriment of the Philippines' more than 170 indigenous languages. The Philippines is a good example of a scenario that has played out around the world in the last 500 or so years, especially where a conquering or colonizing power has laid claim to an area inhabited by a great diversity of indigenous peoples: the colonizer's language first becomes the lingua franca, and then the majority language over several generations. During this time, smaller languages, one by one, fall by the wayside. This is certainly the case in North America as well, where prior to first European contact, a rich variety of languages flourished:

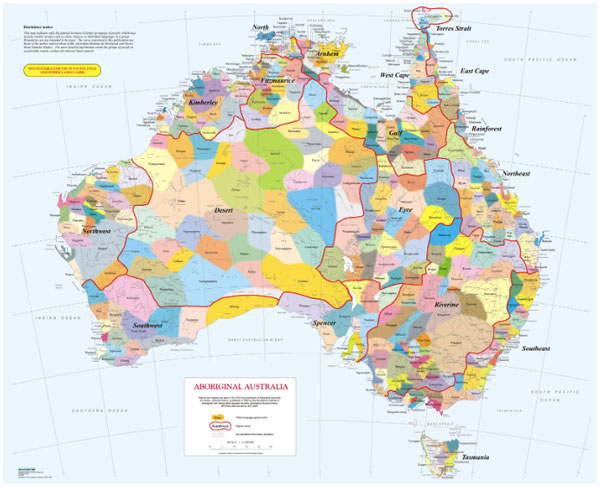

Today, however, most of these languages are extinct, and the few indigenous languages still spoken in North America struggle for survival. A similar situation exists in Australia, once home to an astonishing diversity of aboriginal languages (more than three hundred, representing more than two dozen language families).

Today in Australia, fewer than 150 Aboriginal languages enjoy significant use and only a dozen, spoken in the most remote and isolated areas of the continent, are still being transmitted to children. All others are highly endangered.

Viewed in a historical perspective, it's easy to see that linguistic diversity is the natural state for humanity, just as biodiversity is the natural state for the biosphere. Both of these natural states are threatened by various forces of modern civilization. We appreciate today the great value in defending biodiversity against the forces that threaten it: climate change, overexploitation, monoculture, and pollution, to name a few. Ideally, 2019 can be the year in which we begin to focus on the threats to linguistic diversity and institute measures that will insure its survival.

Species of plants and animals emerge as specific responses to the environments in which they evolve. Natural selection bestows on every plant and animal the unique adaptive mechanisms that enable it to thrive in its niche. When a plant or animal species goes extinct, the world loses whatever particular and unique characteristics it possessed, and may have contributed, to the overall balance of nature and the well-being of the environment. The same is true of languages: they emerge naturally in all human populations, and each of them has unique characteristics that endow their speakers with the ability to efficiently express the essential values of their culture.

What can any of us do to contribute to this effort? Especially when we consider the fact that we are speakers, and in all likelihood, native speakers, of one of the biggest and perhaps the bossiest of all languages in the world: English. Nothing is going to diminish the role of the majority languages in the world today: Chinese, Spanish, English, Hindi, Arabic. Happily, however, there is something that everyone can do to encourage language diversity and create an environment in which any language can flourish. If you have particular skills or inclinations, there's a lot that you can do. Here are some examples:

- If you're a linguist or a computer scientist, there are huge amounts of work to be done (mostly university based) in developing software and databases that can serve as repositories for endangered languages and tools to study them.

- Do you speak, or have access to, a speaker of an endangered language? You might want to check out the Endangered Languages Project to see if there's something you can contribute. You might also want to keep an eye on a program of the National Science Foundation called Documenting Endangered Languages. It makes grants for research proposals on work with indigenous languages under threat.

- You can register yourself or your organization with the 2019 Unesco program if you have something concrete to contribute to it. The forms behind the links give you an opportunity to get creative and tell the program's organizers what you have in mind.

If all of the foregoing seems above your pay grade, do not despair! There is something that everyone can do to contribute to linguistic diversity. You can, for example.

- Learn another language. All research supports the fact that bilingualism and multilingualism give great benefits to speakers in all areas of life. The tools available to language learners today are light years beyond what they used to be: YouTube videos, online courses, and apps such as Duolingo and Babbel bring language-learning within easy reach of everyone.

- Encourage the use of language diversity in your community. Hearing a language you are not familiar with is a common urban experience in most parts of the world, but it may be seen as alarming in less diverse places. The more that we encourage linguistic diversity everywhere, the further we can distance ourselves from bizarre incidents in which speakers of a nonmajority language are viewed as possible criminals.

At the end of 2019, still a whole year away, it will be nice to be able to look back and say that we all made progress towards enriching and strengthening the world of human languages.