Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

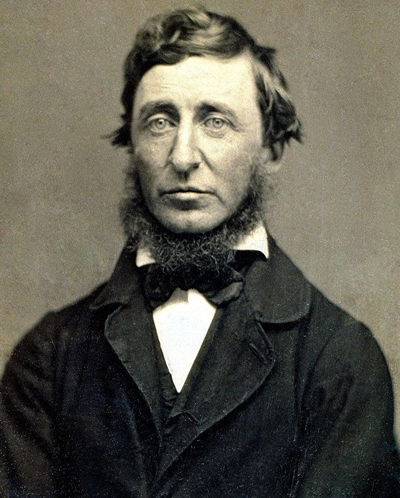

Be Thorough, Like Thoreau

July 12th marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Henry David Thoreau. It is a suitable time to examine his legacy, which comes to us almost entirely in the form of his writing. Indeed, if Thoreau had not written so eloquently and skillfully about the relatively small events of his circumscribed and rather short life, we would not even know who he was. His career should be an inspiration for anyone whose goal is to be a writer but who is stuck on the question: "What should I do?"

When Thoreau graduated from college in 1837, he faced a situation like the one that many of today's college grads find themselves in: there were few jobs available, and he did not think himself temperamentally suited for any of the jobs he could find. He ended up taking a job as a schoolteacher but resigned after two weeks, after a disagreement with a school administrator. So eventually he settled into working in his father's home-based pencil factory. Failure to launch? It's not a new thing.

Thoreau was fortunate in having an eminent neighbor who took an interest in him: the poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson, about 15 years older than Thoreau, was already established as a respected lecturer and writer and he proved to be a great role model for Thoreau: the writing life that Emerson enjoyed was the one that Thoreau was looking for. With Emerson's help (he owned the land), Thoreau built a cabin on the shore of Walden Pond and moved into it in 1845, with the goal of writing a book and conducting an experiment to see if he could lead a very simple, solitary life.

The two years that Thoreau lived at Walden Pond proved to be the making of him. Out of that experience came what are probably his two greatest works: the book Walden, and the essay which is popularly called Civil Disobedience. These two works are among the most read in American university courses today. Both of them were published before Thoreau reached his 40th birthday.

The question that today's aspiring writers might consider is this: how do you go from being an obscure youth with an unused college degree, still living with your parents, to becoming one of the more celebrated writers in American history? For Thoreau, the answer was dedication, courage, tenacity, and striking originality. Regarding his decision to live a life of seclusion at Walden Pond, he wrote:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

The remarkably clear thing about this reflection of Thoreau (he was not yet 30 when he went to live at Walden) is his vision of what he wanted to accomplish: live the Spartan life, and then publish what he learned, give a true account of it.

Could you still do this today? Would you be able to take your smartphone with you? Would there be free Wi-Fi? Thoreau's experience of living in the woods is far removed from what most young writers can imagine today. Indeed, that is one thing that makes his work so compelling to modern readers. But is it futile in today's world to strike out in some original way and write about it compellingly, with the hope of eventually leaving a lasting impression on the literature of your culture? Thoreau may not have set out to achieve immortality, but the quote above expresses his determination to go where no writer had gone before, and the result rewarded the effort. It's too late today to be revered as the father of American Nature Writing, as Thoreau is, but there are surely other experiences that are not yet explored.

Thoreau's other great enduring work, his essay Civil Disobedience, is also remarkable for its influence. Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Leo Tolstoy, and John F. Kennedy all wrote about its influence on them. His main subjects were his objections to slavery and to the Mexican-American war and his compelling argument is that it is our duty as citizens to avoid being complicit in the unjust, unfair, or malevolent works of the government we happen to live under—even if that means contravening laws.

In the essay he writes about one of his own acts of civil disobedience, his refusal to pay the poll-tax because of its implied support for a government that tolerated slavery. Because of this, he spent a night in jail, having been nabbed off the street when he wandered into Concord one day from his cabin on Walden Pond. It was a small price to pay (someone else took care of his poll-tax) and it is a small part of the essay, just a paragraph woven into the overall narrative. But it drives home Thoreau's larger points by making it clear that he wasn't just phoning it in; he was expressing the importance of reconciling conscience with civil obligation in a way that he lived himself.

It was fortunate that once Thoreau settled on what he wanted to do with his life, he wasted no time in doing it. Because of tuberculosis that he contracted in his late teens, his health was never robust and he died at age 44. He never married, had no children, never had what people today, or even of his day, would call a proper job (barring his brief stints at school-teaching), and he did nothing in his life that would merit a mention in most history books. No one considered him good-looking, and he seems to have had only one practical skill: carpentry. Despite that, he is the subject of several biographies and subject at the core of many websites. His writings are all still widely available, widely read, and widely translated.

So for today's aspiring writer, what is the take-home from the life of Thoreau? Here's a handy list:

- Develop at least one practical skill from which you can draw a casual income. This will go a long way towards buffering you from criticism, especially from people you rely on for support.

- Decide what you want to write about.

- If that doesn't come, do something that is worth writing about.

- Write.

- Repeat from step 2.

Thoreau fell ill for the last time after "a late-night excursion to count the rings of tree stumps during a rainstorm," according to his Wikipedia biography. Why would a person do such a thing? Surely, because he intended to write about it.