Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

Farewell, My Lovely Distinction

Linguistic prescription (or prescriptivism) is out of fashion these days. Dictionaries, language pundits, and trophy academic linguists all decry the ex cathedra pronouncements about usage from rule-bound curmudgeons of the past who imagined that they could put fetters on language change.

I would like to consider myself among the modern vanguard, letting language take its natural course and evolve as its owners — that is to say, its speakers — allow it to. But at the same time, I spend hours every week at the rock face of language change — that is to say, in classrooms full of young people — and while there, I cannot but lament the passing of some niceties of English.

In my hours away from the classroom, while I ponder weak and weary over many a quaint and curious locution of these same young people, I cannot help marking what I take to be either mistakes or bad choices, in the hope that I might influence the future of our beloved tongue. It's (or should I say: Its) all in vain, I know. But here are some of the things that bug me.

"Based on" and "based off"

If you consult the Google Books Ngram Viewer for "based on" versus "based off," you'll see that the frequency of "based off" is negligible in printed literature. Which suggests that there is still time and an opportunity to correct the tendency of young people to say things like "Dr. House is based off of Sherlock Holmes" or "You will need to lookup a value in a table based off two values."

But if you listen to young people talk, you will know that there is in fact no such hope. I teach some of the best and the brightest — science and engineering whiz kids — and their speech and writing is all based on thinking that "based off" is the new "based on." I do still mark it in their papers. When I talk about it in class, I get a bemused look, which I translate to mean "You'll die someday and then no one will care about this."

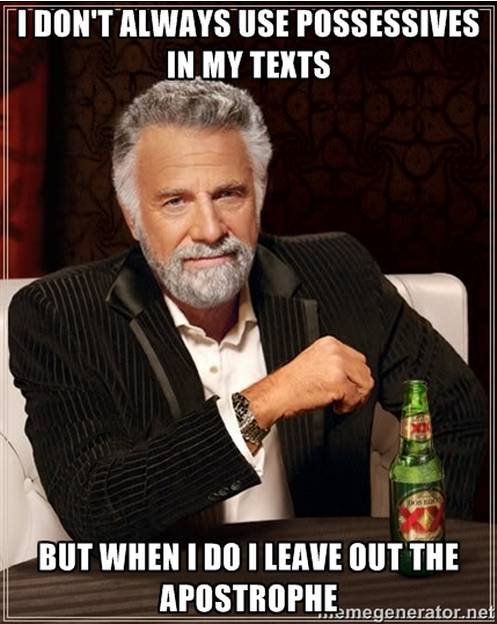

The apostrophe in possessives

It was shocking to me, initially, to note that neither incoming college freshmen, nor graduating seniors, pay much attention to inserting apostrophes to distinguish possessive nouns. I regularly get sentences like "The film shows the importance of fitting in through one mans failures to do so." Of course I mark them, as a small exercise in futility.

I think it likely that the apostrophe will eventually disappear from possessives, because in fact it is not needed. A sentence in which the possessive apostrophe is required to disambiguate a plural from a possessive is rare: syntax nearly always does this, and when you have a reliable higher order disambiguator (syntax), you don't really need a lower order one (orthography).

I blame texting for this development more than anything. Many phone keyboards require extra keystrokes to insert an apostrophe, and an efficient communicator will probably consider: why bother. Indeed, I can truly say of myself that

It's versus its

It's hard to let go of this distinction because of its simplicity. In speech it is rare for there to be any confusion between it's (=it is) and its (=belonging to it). It should, therefore, take only a fractional second's thought for the writer to arrive at the correct form, and either insert or omit the apostrophe.

But this is a fractional second that my students often cannot be bothered with. And again, since syntax will nearly always force an interpretation of one or the other, it is a valid question to ask why we persist in keeping two forms to trip up writers.

Affect and effect versus impact

Perky meteorologists regularly warn us about how approaching weather may impact our weekends, and financial analysts may be concerned that lack of sales growth will impact profitability. Said professionals probably realized long ago that rather than come to a firm and confident stance about the fiddly differences between the verbs and nouns effect and affect, it's a lot easier to just toss them both out the window when you need a verb or noun and use impact instead.

The impacts on language are unfortunate. But unavoidable. My students all get fidgety when I point out their errors with effect and affect, and they realize as so many others have: it's just easier to be an impactor.

Dangling modifiers

Sensitive teachers should always be alert to two deadly classroom syndromes that are to be avoided, and immediately headed off if they are detected. I call these the MEGO (my eyes glaze over) and the DITH (deer in the headlights) syndromes.

Outbreaks of MEGO arise immediately in my classroom if I use a grammatical term, such as appositive or participial. DITH happens if I start to scan the room for a student to call on and ask that they (yes: they — see next) give a grammatical analysis of a sentence I have written on the board. The sentence in question is usually one that includes a participial clause whose subject requires the reader to set off on an unfruitful expedition; a sentence like:

The argument that churches deserve tax breaks makes sense at first glance, but is flawed when analyzing it deeper.

The when analyzing it deeper clause needs sensible governance by the subject of the main clause. Without this, the sentence fails grammatically. It needs to be reworded as:

The argument that churches deserve tax breaks makes sense at first glance, but is flawed when we analyze it deeper.

or:

The argument that churches deserve tax breaks makes sense at first glance, but I find when analyzing it deeper that it is flawed.

But why? Because the grammar of English says so. The wrong sentence forces extra processing on the reader, who must supply the missing subject of analyzing. That's actually not such a hard job — or so my students seem to think, because they foist this job onto their readers all the time. The hard job for them is understanding why the sentence is not correct. So I wonder if this civilized rule can be preserved for long in English.

They with a singular antecedent

I will close with a battle that I did not engage in, and that I can say has already been rightly won by common sense, and that is they used with a singular, somewhat nonspecific antecedent.

I do not object to sentences like Would the person who left their backpack please pick it up? or Any professor who says they never make a grammatical error is deluded. The first sentence has the under-specified antecedent person. The second has the somewhat indefinite antecedent any professor.

I do, however, still object to sentences like An individual who thinks they are infected should see a doctor, because for me this still just doesn't sound right. An individual, in my mind, cannot be a they. But my students disagree with me on this, and when I'm slobbering into my sippy cup in a nursing home some years hence, I don't expect that many speakers and writers will be bothering about whether individuals can be theys, because all of them will be.