Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

Is Now and Ever Shall Be

Oxford University Press has reprinted the first edition of a great classic — H. W. Fowler's A Dictionary of Modern English Usage — and we've been enjoying the book in the Lounge. It reproduces the text of the original, along with a new introduction and 25 pages of notes that refer to about 300 entries in the first edition, reflecting ways in which the language has changed since the 1920s, when Fowler's work first appeared. The notes are written by David Crystal, whose credentials as a contemporary authority on English are unassailable.

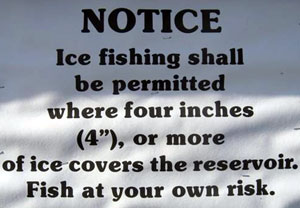

There is never a reason not to consult Fowler about usage: whether you find what you were looking for or not, you'll walk away from his text amused and edified in a way that you weren't when you went to it. We found an occasion to consult him the other day when we noted this sign that's just appeared, down the road a bit from the Lounge:

Shall be permitted? Today's mainstream English speaker would simply say "Ice fishing is permitted..." What's the deal?

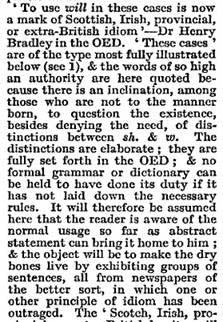

Fowler has a lengthy entry at shall that treats shall & will, should & would. With characteristic wit, he notes:

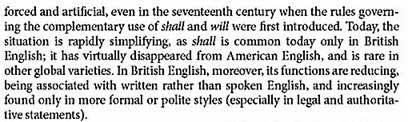

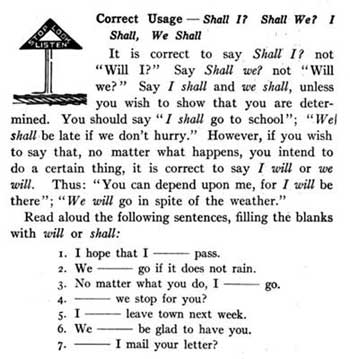

He then goes on to delineate the distinctions between shall and will, rendered in various constructions as should and would, for three pages, during which the modern reader will come to lament that an important distinction of modality available to earlier refined speakers of English is now lost: Fowler has it that will was reserved for use in sentences where "intention, volition, choice, etc" are involved, while shall is for use in sentences of "plain future or conditional statements & questions in the first person." But is the distinction really lost, and perhaps more importantly, did it ever really exist? David Crystal, in his update of this entry, says that there is abundant evidence of this distinction being

He goes on to note that shall still holds its place in first-person questions, wherein the speaker signals a desire for input about a possible course of action (i.e., "Shall I leave the light on?"). This use, though concerned with the future, is essentially a modal use of shall that all dialects of English find useful, and it clearly serves a different function than the somewhat unlikely "Will I leave the light on?"

We would disagree with Mr. Crystal that, aside from the foregoing use, shall has "virtually disappeared" from American English. Even formal and polite Americans don't give it the exercise that Britons give it in speech, but shall is still common today in American English in many of the same contexts as it is in Britain — and our sign is an example of this. How and why does it survive, when nearly all speakers routinely use will as the all-purpose future auxiliary verb?

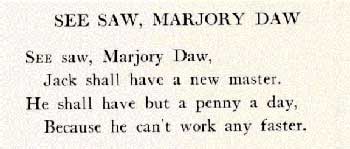

Though very few speakers today use it in a prescribed way, shall leaves an indelible impression on the minds of developing native speakers of English in many forms, starting early in life. There are, for example, nursery rhymes:

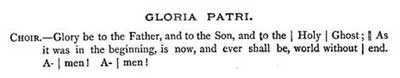

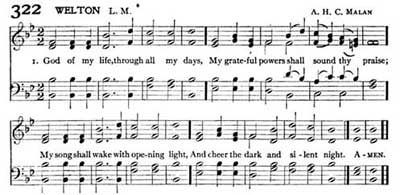

Prayers and hymns:

Even modern biblical translations, while largely dispensing with archaic shalt (the very sound of which may conjure visions of hellfire) still seem to prefer shall over will, no doubt for its authoritative tone. (See, for example, these parallel translations of Exodus 20:16, the 9th commandment.)

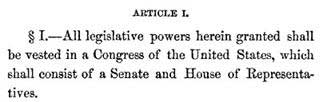

No sooner do Civics lessons begin in middle school than students get repeatedly pinged by shall in great historical documents. It occurs only once in the Declaration of Independence but nearly 200 times in the U.S. Constitution, nearly all of them in a "legal and authoritative" way, starting in Article 1, Section 1:

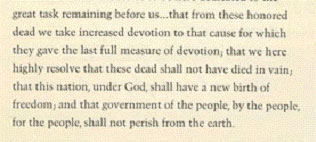

Perhaps inspired along similar lines, Abraham Lincoln uses a famous shall triplet in the peroration of the Gettysburg Address:

Greta Garbo in "Grand Hotel":

I shall dance and you'll be with me and then — listen — After that you will come with me to Lake Como, I have a villa there. The sun will be shining. I will take a vacation — six weeks — eight weeks. We'll be happy and lazy. And then you will go with me to South America — oh!

Joan Crawford in "Mildred Pierce":

I shall prevent this marriage in any way that I can.

You can find scores of other examples with the search "you shall" on script-o-rama.com, where it is obvious that Hollywood is the true master of the "decorative and prophetic" shall. Alternatively, there's a pretty good case to be made that what Fowler said in 1926 still holds true today:

The time-honoured 'I will be drowned, no-one shall save me', so much too good to be true, is less convincing as a proof that there are people to whom the English distinctions mean nothing than the discovery that shall & will, should & would, are sometimes regarded as good raw material for elegant variation.