Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

Patches

We rarely shine the spotlight on a single word in the Lounge but this month we have a special honoree: the noun patch. We've heard a couple of startling uses of patch recently and it got us thinking about what a great word it is, and how well it exemplifies the genius of language and the genius of English.

There are few things not to love about patch: it's short, and it's easy to spell and pronounce by a speaker of any language. It occupies a spot, a bit past the middle, of the 5,000 most frequently used words in English. It has numerous rhymes and it has been kicking around English since the 14th century (the verb patch, derived from it, first appears in the 15th century). Patch has uncanny sound sense, making it easy for learners of English to associate with the things it denotes: if you repeat patch to yourself, mantralike, it takes a very long time before its meaning fades and it becomes a mere sound cluster. But what is a patch? Ask a dozen people and you will probably get half a dozen answers, all of them correct in their own way.

The Oxford English Dictionary and Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary each have 21 senses for the noun patch. The college dictionaries and the Visual Thesaurus settle for a more modest nine to twelve, and pocket dictionaries may get by with only two or three. The meaning of patch that really interests us, however, is not one of these numbered and delineated senses, but the one that lurks in the native speaker's mental lexicon: what qualities must a thing have in order to earn the name patch? What are the defining qualities that make a patch a patch, and not something else?

Adam Kilgarriff, a computational linguist much revered in the Lounge for his contributions to lexicography, wrote a paper called "I Don't Believe in Word Senses" in which he argues convincingly that word senses do not really exist – that is, they do not exist independently of the criteria we use to differentiate them: they exist only relative to a task for which they are needed. This idea is especially pertinent to very old "homesteader" words like patch that have had many centuries to establish, expand, and hold their claim on a conceptual space in the mind. Through each encounter with the linguistic symbol patch and its real-world objects, we develop a notion of what a patch is. We all know different things not really very like each other in some respects that are called patch in English, but if called upon we can probably justify the claim to the name for any individual sort of patch, whether it be of the bad, bald, nicotine, or vegetable variety; certain qualities recur in the many different things we call patch.

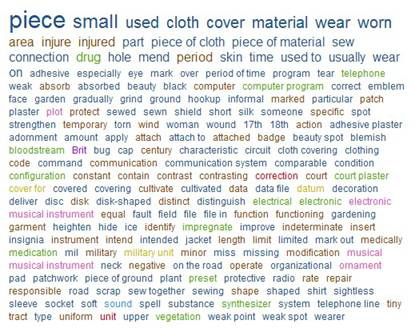

To get a better idea of the main qualities that constitute patchiness for the English speaker, we dumped all the definitions of patch from a handful of dictionaries into the Visual Thesaurus VocabGrabber to produce this frequency-sorted wordcloud:

The words in the first three rows are a pretty good snapshot of what a thing has to be, have, or do in order to be called a patch in English – but only in English, mind you: it's instructive to look at a wordmap of patch with a couple of other languages displayed, to illustrate that the space occupied by patch in the English speaker's lexicon doesn't really map to a corresponding space in another language: they all require multiple terms to translate the various things that English speakers call a patch.

This brings us to the two recent usages of patch that grabbed our attention. The first was in relation to the Toyota recall debacle, in which some media outlets reported that what was required to fix the problems associated with brake failure was a software patch. We don't find that Toyota itself used this terminology, and we would be surprised if they did. Software patches have been around since the 1950s and the original coinage was an apt one. A software patch – that is, "a small piece of code inserted into a program to correct a fault (usually temporarily) or to enhance the program" (from the Oxford English Dictionary) – has many of the qualities we associate patches: it's small, it's a "piece," it has a reparative function, it's probably temporary. Software patches are great for computers that sit on our desks, and even for satellites that wander lonely as clouds far above the horizon. Not so much though, to our minds, for things that hurtle down the freeway at excessive speeds, carrying precious human cargo. You want to entrust that to something called a "patch"? A patch is great for making something usable that has been disabled, but when you designate something a patch you can't escape the other attendant baggage of the word: of being makeshift, temporary, and typically employed because a more enduring or dependable solution was not available or worthwhile. This is not what you want to hear about the only thing that stands between you and roadside carnage.

The other use of patch that pricked up our ears was in an interview with a television actor, in which he reported that while filming a nude scene he was actually wearing a "modesty patch." This was a term previously unknown in the Lounge (where expanses of flesh are never on view), but upon hearing modesty patch for the first time we knew exactly what it was and what it was for. Why? Because it is so perfectly named. Those seeing the term here for the first time will also have no difficulty in surmising that a modesty patch is a small garment, worn so as to enable an actor to maintain (or feign) a shred of modesty by appearing to be nude to the camera, but not completely so to fellow actors and others on the set. We do not know who coined "modesty patch," but if we ever meet this person we will heartily congratulate him or her for the perfect aptness of the term. While perhaps not a career milestone for patch, "modesty patch" calls upon the most of the essential qualities of patch and furthers its reach over real-world objects, while further reinforcing the small but definite domain it occupies in the mental lexicon.