Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

Quo Animo? The Case for Studying Latin

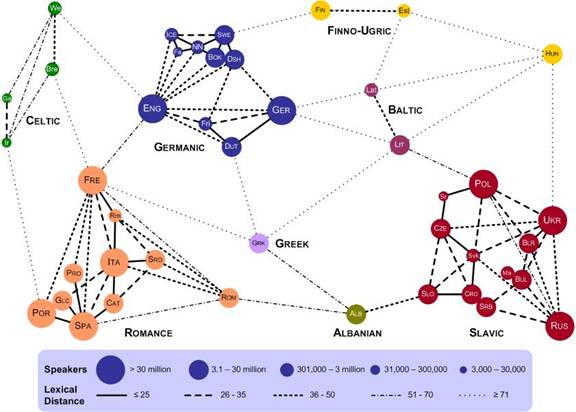

If you read the Visual Thesaurus Word of the Day you know that it often explores word origins. Even without keeping count, you are probably vaguely aware that the language mentioned more often than any other besides English is Latin. Statistics about the English lexicon reflect this. Estimates vary in particulars but all scholars and statisticians agree that more than half of English vocabulary — around 60% is a popular figure — has ultimate Latin roots. English is unique among Germanic languages in having such a short lexical distance (that is, a high percentage of cognate vocabulary) with a language in another family, as this recently posted graphic from the blog Etymologicon shows.

In this case, the lexical distance shown is to French, a Romance (i.e., Latin-derived) language. Latin is not shown in the chart because it carries that sad epithet of tongues no longer actively spoken: Latin is a dead language, without the possibility of newborn speakers who will learn it as their first language. Latin is alive today only in a few specialized contexts where it is kept on life-support by those who have a vested interest in its preservation: mainly, top-tier ecclesiastics of the Roman Catholic Church, and teachers and scholars of Latin.

English has always borrowed freely — you might even say indiscriminately — from all languages and this might suggest that over time, the predominance of Latinate words in English would decline. This is probably not so. English borrows as happily from the dead as from the living, and Latin (along with classical Greek) still provide rich pickings for new coinages in science and medicine.

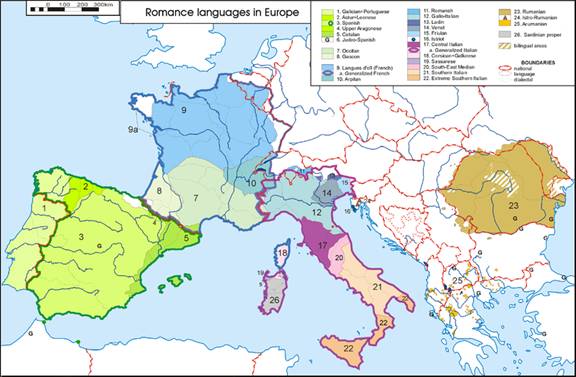

That there even are teachers and scholars of Latin today is testament to the influence that the language once had, as the language of the culture and empire that dominated Europe and its border areas for centuries. Latin is the parent of many of Europe’s most important languages today, as can be seen in this chart:

The study of Latin, however, has been in general decline for centuries. Latin was once taught in grammar schools and familiarity with it — if not mastery of it — was a prerequisite for university admission. At the turn of the twentieth century, more than 50 percent of the public secondary-school students in the United States were studying Latin. Today, there are colleges and universities where Latin is not offered, and the availability of Latin in secondary education, at least in the English-speaking world, is a hit-or-miss affair. I attended high school in a Midwest farming community of 5,000 in the 1970s, where the foreign languages offered were Spanish, French, German, and Latin. Today that high school — in a community that has grown to more than 7,000 — offers only Spanish and French.

Should Latin be allowed to fade from the foreign-language curriculum to the degree that it has? League tables from 2009 for foreign language pedagogy in the US show Latin to be cellar-dwelling in the top ten, and with the smallest increase in students from three years earlier:

Language |

Fall 2006 |

% change |

Fall 2009 |

% change |

|

1. Spanish |

822,985 |

10.3% |

864,986 |

5.1% |

|

2. French |

206,426 |

2.2 |

216,419 |

4.8 |

|

3. German |

94,264 |

3.5 |

96,349 |

2.2 |

|

4. American Sign Language |

78,829 |

29.7 |

91,763 |

16.4 |

|

5. Italian |

78,368 |

22.6 |

80,752 |

3.0 |

|

6. Japanese |

66,605 |

27.5 |

73,434 |

10.3 |

|

7. Chinese |

51,582 |

51.0 |

60,976 |

18.2 |

|

8. Arabic |

23,974 |

126.5 |

35,083 |

46.3 |

|

9. Latin |

32,191 |

7.9 |

32,606 |

1.3 |

|

10. Russian |

24,845 |

3.9 |

26,883 |

8.2 |

As you read through the list of languages sequentially, compelling practical reasons for studying each of them may come to mind. Spanish is effectively a second language in the United States today and is useful to anyone who lives in the southern half of the country, the West Coast, or in any of the northern metropolitan areas. The continued popularity of French and Italian may be somewhat anomalous, given the declining economic and political influence of the countries where they are spoken, but the cultural heritage of French and Italian (both Romance languages) will probably keep them popular for years to come. The presence of Arabic and two Asian languages on the list are testament to globalization and the emergence of economic, cultural, and political influences that the West may once have viewed as marginal or exotic.

With so many foreign language opportunities in education today, the decline of Latin is probably not surprising; it’s possible that it simply reflects a supply-and-demand problem. Students don’t enroll in Latin courses, the courses don’t form, and after some time it may be inexpedient for schools to retain the faculty whose job it is to teach Latin. That’s certainly one conclusion you could draw from a 2006 story in the British tabloid the Daily Mail, in which it was reported that teachers told students to avoid Latin because it was too hard.

Latin is definitely not a walk in the park, even for native speakers of Romance languages. Latin is highly inflected, with three genders, five to seven noun cases (scholars vary on how they should be analyzed), four verb conjugations, six tenses, three persons, three moods, two voices, two aspects, and two numbers. A question that naturally arises then is this: why should students toil and sweat to master a difficult language that they will never have an opportunity to speak in any but an artificial context?

Seekers of answers to that question can find numerous lists of reasons online that frame the study of Latin as a ticket to success: for increasing vocabulary, scoring better on standardized tests, learning other foreign languages. One education blog, without specific reference to statistics, says that "Latin has made a remarkable comeback in U.S. schools at the start of the twenty-first century." Perhaps this is so. But what would actually constitute a comeback, and is it a comeback or a dead-cat bounce? It seems unlikely that we will return to the day when half of high-school students are studying Latin. The survival today of Latin scholarship from the time of the decline of the Roman Empire may simply be the slowly dying ember of a fire that once burned brighter than any other. The modern world has set other priorities for the development of productive citizens that make the study of Latin look esoteric, impractical, or unnecessarily expensive. Sic transit gloria mundi. Ironically perhaps, the cohort that would probably most benefit today from the study of Latin are those who make another language their central focus: English majors.