Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

She Created a Monster

I have love in me the likes of which you can scarcely imagine and rage the likes of which you would not believe. If I cannot satisfy the one, I will indulge the other.

― Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Frankenstein

Long, cold winter nights lend themselves to absorption in a good narrative and if you're looking around for one, you could hardly do better than Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. Mary Shelley's novel was published 200 years ago, on January 1, 1818, and it is hard to think of an imaginative work that has had a greater influence on popular culture. It's a good example of how the best creative writing spawns even more creativity, and in this case, gave birth to a whole genre of creative endeavor.

The paper trail documenting the creation of Shelley's novel is unusually complete and it gives us an opportunity to examine how various sparks of inspiration, memory, knowledge, and constraint were transformed into an enduring work of genius whose influence seems never to abate. Surely every adult today, and most every child, conjures a vivid image at the mention of Frankenstein, and while the image may be a bit removed from the one that first arose in Mary Shelley's fervid imagination, it will surely share many characteristics with the original.

Mary Shelley, the precocious daughter of political philosopher William Godwin and proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, began a romance with the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley when she was only 17 (he was 22). The couple traveled together in Europe, taking in grand-tour sites along the Rhine including Frankenstein Castle. A fact they learned about the castle is that it had once been home to an alchemist.

In the summer of 1816 (Mary turned 18) the couple rented a villa on Lake Geneva with friends. Finding the weather inclement, the group often amused themselves by reading ghost stories to each other. It was Percy Shelley's idea that each of the villa's tenants should write their own ghost story as a contribution to their mutual entertainment. That bit of gentle peer pressure was the spark that ignited a considerable pile of tinder already in Mary Shelley's mind.

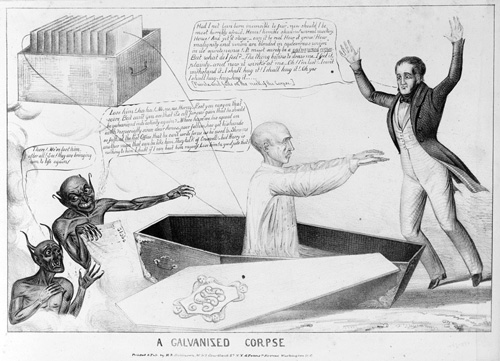

A new idea in the early 19th century was galvanism, which explored the connections between electrical current and physiological processes. Strange as it may seem, people speculated that an inanimate corpse might be "galvanized," that is, animated and brought to life, by the use of electrochemical means, as is spookily illustrated in this 19th century cartoon.

Unable to sleep one night during the rainy summer in Geneva, Mary reported that she "beheld the grim terrors of a waking dream," in which she imagined Dr. Frankenstein (a character she invented) bringing to life the patched-together body he had assembled by grave-robbing and other means. Here, certainly, was material for a first-class ghost story, and Mary had a place to begin.

Her obligation to her housemates was satisfied and it's possible that Frankenstein might have been just one of hundreds of 19th century ghost stories that are now gathering dust in musty old libraries, except that its author did what many great writers have done: she became completely obsessed with her subject, and built around her initial, horrifying vision, a complete narrative that encompassed everything from the backstory of Dr. Viktor Frankenstein, the monster's creator, to the moral, ethical, practical, and social implications of inadvertently releasing an amateurly-constructed humanoid into society.

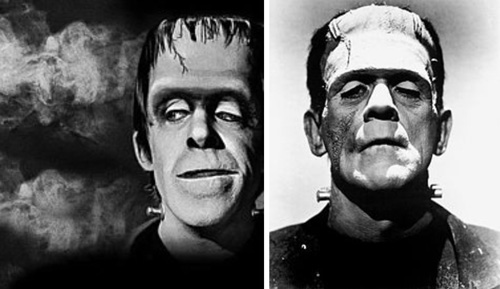

As a modern reader you are likely to have learned who "Frankenstein" was initially on the basis of the popular culture version. It might have been a Halloween costume, or a comic book or cartoon character. Perhaps you watched The Munsters in the 1960s or in reruns―the silly sitcom that featured a family of agreeable grotesques including Herman Munster, played by actor Fred Gwynne. Gwynne's appearance was modeled on the makeup job applied to Boris Karloff in the 1931 film Frankenstein, the film that must be credited with giving legs to the modern Frankenstein franchise.

The 1931 Frankenstein was the first of four classic horror films from British director James Whale; the last of the four was the 1935 Bride of Frankenstein, which was also inspired by a subplot in Shelley's book. Both of these films have held up well over more than three quarters of a century and they have inspired imitators, sequels, and parodies.

One of the best films featuring a Frankenstein monster is based not directly on Shelley's book but rather on another novel: Father of Frankenstein, published in 1995 by American writer Christopher Bram. In that book, novelist Bram speculatively explored the last days of the life of director James Whale. That novel is the basis of the 1998 film Gods and Monsters, starring Ian McKellen as the now-retired director Whale, living in poor health, misty nostalgia, and encroaching mental debility in California.

The idea of the well-intentioned humanoid gone awry is now so thoroughly integrated in the popular imagination that it lives largely independently of reference to the original Frankenstein. Take, for example, the 2015 film "Ex Machina," in which a mad-scientist type, living alone a fortress-compound in the middle of nowhere, attempts to create perfect female androids, with dire consequences. The film makes no mention of Frankenstein, but critics and viewers clearly got it. A good example is this review on IndieWire.com, Alex Garland's 'Ex Machina' Delivers a Modern Day Twist on Frankenstein.

Another completely different lens on the influence of Frankenstein in popular culture is in the splash page the Google Ngram viewer. The default search there is on three names―Albert Einstein, Sherlock Holmes, and Frankenstein―and the graph clearly shows that Frankenstein has come out ahead of the other two names in frequency of mentions in printed literature since the 1960s. It seems that speakers of English can never get quite enough of "Frankenstein". The name has even spawned its own combining form, Franken-, which can be a way of designating something of monstrous proportions ("Frankenstorm"), or a disparaging way of designating a food produced by dubious artificial means: Frankenfood, Frankencrops, Frankensalmon.

What accounts for the emergence this fully fledged and widely shared cultural meme from the 200-year-old first novel of a young writer? The enduring appeal of Frankenstein is surely in Mary Shelley's thorough, imaginative, and compassionate journey into the ramifications of her late-night, eerie vision. She took a very far-fetched "what if?" and spun out its implications into a complex narrative that still reverberates and inspires new "what ifs?" two hundred years after the fact.