Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

War and Words

In fifty years from this time, the American-English will be spoken by more people, than all the other dialects of the language.

—Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, 1806

The National Museum of Language near Washington, D.C. is putting together an exhibit on the role of the War of 1812 in the development of American English, as we approach that war's bicentennial (or bicentenary, as they still say on the other side). In the Lounge we've been exploring ideas with the museum, and this month we wanted to share some of our findings.

To set the scene on a war whose name doesn't give many mnemonic clues: the United States was quite newly fledged as a country in 1812, and consisted of only 18 states: the 13 original colonies, plus Vermont and four states that were then considered on the western frontier: Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, and Louisiana. Relations with Great Britain were not at all settled in the wake of the revolutionary war that had ended about 30 years earlier, and British meddling in US affairs was rife. The War of 1812 — begun officially on June 18th when the US declared war on Britain — is sometimes dubbed the "second war of independence," in which the US established itself unequivocally as a sovereign power among its peers. But how was English faring during this time?

Events of the day aside, the two major dialects of English had begun their divergence long before — nearly 200 years earlier, with the beginning of continuous settlement of North America by English speakers. The growing differences in the dialects had come to the notice of some speakers on both sides of the Atlantic by the early 19th century, and the first prominent, distinctly American writers — Washington Irving (1783-1859) and James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) — had come to the favorable notice of Europeans.

However, the prevailing opinion about American English from the source that regarded itself as authoritative — namely, British intellectuals — was not so favorable. The ink was barely dry on the Declaration of Independence before British pundits were slamming American English at every opportunity (as documented by H. L. Mencken in several pages that begin here). A writer in the Monthly Mirror of 1808 lamented "the corruptions and barbarities which are hourly obtaining in the speech of our trans-atlantic colonies." Authors of such comments were the very people that Noah Webster, in 1789, had already denounced, when he wrote of England: "the taste of her writers is already corrupted, and her language on the decline."

These slings and arrows were exchanged at the high end of the transatlantic discourse of the time. At the low end — the language of the American or Briton on the street — there was probably little awareness of or concern for the divergence of the dialects, and to most speakers the language was still just English. Indeed, the first attestation of the term American English comes only in 1805 (according to Merriam-Webster) or 1806 (according to the OED, whose first citation is from Noah Webster himself, and appears above).

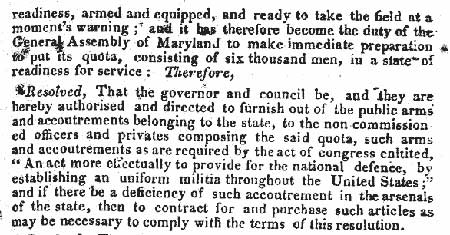

A look at the American English of 1812 finds it looking not that much different from the British English that we know today — at least with regard to spelling. Here, for example, is an excerpt from an 1812 act from the Maryland legislature, authorizing the formation of a militia to support the war effort. Note the spellings authorised and defence:

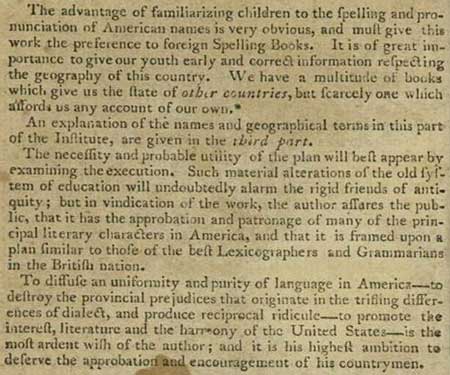

Webster's American Spelling Book (an excerpt is reproduced below) was already in print at this time and widely circulated, but he started out conservatively with the spelling reforms that are now chiefly associated with him, and his first dictionary, whose preface we quote at the top, preserved most traditional spellings. To the degree that the average American thought about it in 1812, English was the language that came to America from England, and anything authoritative about the language, whether in the form of books or pronouncements, probably came from the same place — the country of which many Americans had been subjects until recently. Webster, on the other hand, was clearly thinking along other lines:

Aside from the unmistakable self-promotional aspects, we can see in Webster's words here a clear intention to distinguish American English from its parent, and he did indeed spend the rest of his life pursuing that mission, and plowing the considerable profits from his spelling book into his one-man dictionary mission.

In the same year that the US began its new war with Britain, Webster moved from Connecticut to Massachusetts to begin his life's chief work: his 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language. He advertised his undertaking in an attempt to win subscribers and was largely met with scorn. Even American intellectuals were aghast that he should question the authority of Samuel Johnson, whose monumental dictionary was then about 50 years old. All educated opinion thought that Webster was misguided in the notion of immortalizing an idiom that "sprang from the mouths of the illiterate," rather than from the canon of English literature.

By the war's end — officially in 1815 — Webster's game-changing dictionary was still an undertaking barely begun. The number of speakers of American English had not increased significantly during this time (there was little immigration because of the war), but the awareness of and identity with American English had gained the foothold that it didn't quite achieve during the revolutionary war. The United States achieved a limited military victory, but its real victory in this war was psychological: they had won the war this time with everyone on board — not with the resistance of loyalists, who had made up about 20% of the population in the earlier war — and the consensus now was that being an American and talking like an American was a good thing.

Merriam-Webster's contemporary collegiate dictionary records about 500 new words that entered the language between 1812 and 1815. Only one seems to be a direct result of the war — the transitive use of the verb conscript, first cited in the Connecticut Courant in 1813. The Online Etymology Dictionary, without laying out the paper trail, says that the idiom "eat crow" dates from the War of 1812. Perhaps the greatest lexical victor of the war was the much older word spangled, which got promoted to a plush job that it will keep forever. Francis Scott Key, unavoidably detained on a ship in Chesapeake Bay on a September night in 1814 and compelled to watch the bombardment of Fort McHenry by Royal Navy ships, was moved to write the words that eventually became the national anthem. The epithet "star-spangled," interestingly, goes back to the 16th century but never seems to have been applied to anything but the sky until Key's moment of inspiration for the Star-Spangled Banner.