Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

What Did God Really Mean by That?

Last month I talked about some problems that readers encounter in interpreting canonical language in legal contexts, using the U.S. Constitution as an example. The other area in which canons play a pervasive and highly influential role is in religion. We deal with problems of meaning in religious canons in some ways that don't work in the legal context, where one size has to fit all. In sacred canons, since there can rarely be any fiddling with the text, there is nearly unlimited fiddling with interpretation of the meaning.

The creators or curators of religious canons don't normally make provision for subsequent revision. Instead, they use whatever is available to give their words the imprimatur that should, in principle, minimize doubts around meaning, intention, and authority far into the future. Confidence in the authenticity of religious canons and scriptures, possibly authored by people of the past known mostly by fabulous stories, requires a strong act of faith, but perhaps not as strong as the ones that must precede it. You have to accept first of all that God (in whatever form you conceive him/her/it) exists, and you have to accept that communication from God can be codified or transmitted in the medium of language, which is demonstrably a human invention. That's a subject I waded into before (follow the link), and that readers responded to thoughtfully.

Despite (or perhaps because of) this "set in stone" aspect of religious canons, variations in the interpretation of their meaning, intention, and importance has historically been extremely varied. One reason for this is the principle of plurality. Many doctrines compete for the hearts and minds of devotees, and within any doctrine, many interpretations are possible. As long as those who interpret a text one way can tolerate and co-exist with those who have a different interpretation, all can be well. That doesn't work for legal canons, as we saw, because everyone has to live with the same interpretation that is decided by authority.

Another principle that facilitates conflict-free coexistence of competing or contradictory sacred canons is freedom of religion. If that freedom is missing, religious canons may be perceived to be as burdensome and inflexible as constitutional law. Where that freedom is granted or insisted upon, human creativity gets hold of canonical language and runs with it.

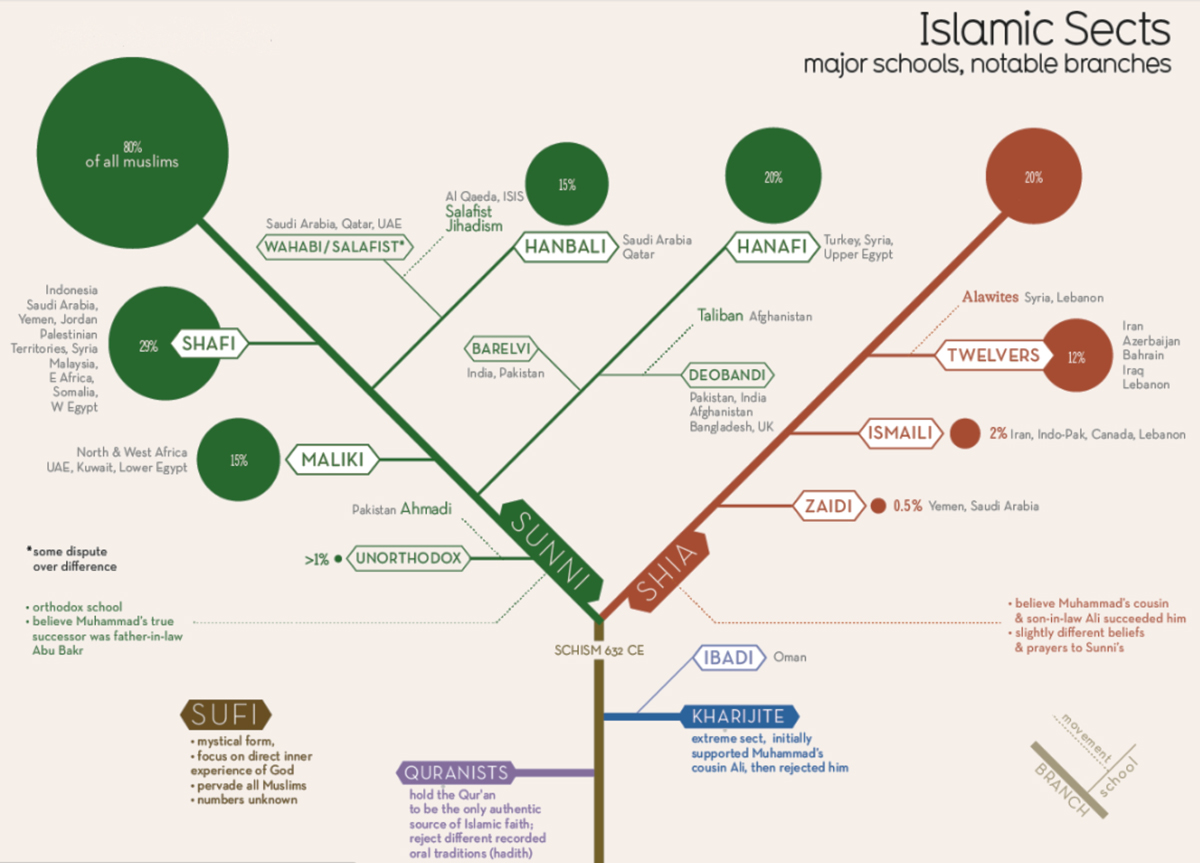

Consider the Qur'an. For practicing Muslims, it represents the revelation of God to the prophet Muhammad, transmitted by the angel Gabriel over a period of more than 20 years. So, spoken by God, transmitted by an angel, and recorded by a prophet: there's not a chink in the armor of those credentials and ordinary mortals may not find standing to question them. You either accept the Qur'an for what it's reported to be, or you don't. Or to put another way, you either are a Muslim or you're not. But if you are, you are not bound to a particular way of interpreting the Qur'an. You can, in principle, choose among the schools and traditions of Islam and find one that accords with your aspirations. Since its emergence in the 7th century, Islam his bifurcated and ramified to where it is now expressed in many different varieties, as helpfully laid out in this infographic.

The situation with the Bible (as popularly understood: Old and New Testaments together) is somewhat different. Its long and complicated history, provenance from many sources, and existence in many versions and languages in which none has hegemony mean that the religions arising from the Bible — Judaism and Christianity, at least — have myriad interpretations of canonical language and ways of expressing its implications and dicta. In Christianity alone there are sects as widely diverse as Quakers and Catholics, Mennonites and Maronites. Such a diversity of faiths exists and persists for numerous historical reasons, but also because, as I noted above, religious canons are subject to nearly unlimited variation in interpretation of the meaning.

It's possible, though not necessarily helpful, to classify Bible-based religions and their sects in scalar fashion, depending on how seriously they regard the language of the Bible. At one end you have Biblical inerrancy or literalism, (popularly: fundamentalism), present in both Christianity and Judaism, in which the Bible is regarded as the inerrant word of God. The other end of that spectrum may hold Biblical language to be merely inspirational, literary, or of historical interest; points of view that are sometimes collected under the term Biblical minimalism. Even with such widely divergent views on the nature of canonical language, coexistence works where tolerance prevails.

Some religious communities borrow a page from the playbook of legal canons and declare that their interpretation of canonical language is the one true and correct way to interpret it, and that all other interpretations are incorrect. This is the foundation of religious intolerance. Such a rigid attitude does not usually enjoy any enforcement mechanism outside of the community that holds the one true way interpretation of sacred texts; the community has to devise its own enforcements and punishments, such as shunning, shaming, or excommunication. Where this sort of religious authority is aggressively asserted with the support of a government, army, or militia, it becomes the foundation of religious persecution.

The great variety of religious canons in the world, coupled with their myriad expressions in faith communities, is a pretty good indication that religion is in many ways a free-for-all. People will, in whatever circumstances they find themselves, find a way to apply canonical language to their present reality in a way that preserves the sanctity of the canon while allowing behavior or views that are accepted as normal. Canons, whether you believe that their prime movers are divine or not, are the work of humans, and are surely among our most imaginative creations. But our ways of interpreting and implementing the language of religious canons are equally imaginative and creative: they answer to our need to build narratives that support our ever-changing ways of looking at and living in the world. The conceit that a particular interpretation of a particular canon has some sort of unique fix on truth is problematic to maintain in a synchronic view, and impossible to maintain in a diachronic view of human experience.