Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

Get Real

“The system of nature, of which man is a part, tends to be self-balancing, self-adjusting, self-cleansing. Not so with technology.”

— E. F. Schumacher

Regardless of where your views fall on the political spectrum, there's a pretty good chance that you subscribe to the idea that we are in a new age of inauthenticity. Both the American Dialect Society and Collins Dictionary declared "fake news" the Word of the Year for 2017. It's now a standard trope in public discourse to acknowledge that the social media enabled by modern technology results in a greatly enhanced ability for all of us to share, and be exposed to, misinformation, the older and less precise term for "fake news".

Since 2017, the two biggest Anglophone communities in the world, Britain and the United States, have both sunk deeper into divided and fortified camps: the Leavers and Remainers in the UK are split around the question of Brexit with their contrasting narratives of its merits and flaws, and the supporters and detractors of President Trump in the US engage in a continuous barrage of accusations of lies and distortions on what each perceives as the other side.

How does language figure in these unfortunate schisms in English-speaking polities? Quite centrally: it's the medium in which nearly every deception and every evasion or distortion of truth is carried out. And language is tailor-made for that task. Nature has a very limited scope for deception, pretty much confined to camouflage in its various forms. But language has unlimited scope for deception because it's already a step removed from reality; it can at best be an imperfect representation of it, and at worst an intentionally malicious falsification of it.

Humanity has developed an arsenal of ways to use language in order to produce some effect that goes beyond accurate and unbiased representation. There's even an argument, often called the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, that language does this by its very nature, without any intention on the part of speakers to distort: in other words, language itself introduces bias by directing our attention or thought to a limited or particular interpretation of what is presented to our senses. But even without linguistic relativity (another name for the aforementioned hypothesis), we have innumerable ways to use language combined with intention to favor a particular reduction or distortion of facts and actual events.

The modern, shorthand name for this general distorting facility is spin, a term that, along with its proliferating compounds (spin doctor, spinmeister, spin room), has seen increasing use since the 1970s. The older and at one time more respectable term for this facility is rhetoric. Aristotle wrote the defining treatise on rhetoric, and it was a required subject of study in medieval universities. "Persuasive rhetoric" and "brilliant rhetoric" were once fairly frequent collocations in English. Today, those are outgunned by "empty rhetoric" and "mere rhetoric". Spin has been a pejorative term from the get-go.

Is there something particular about English that has resulted in the largest populations of native speakers of this language falling into such intractable us-vs.-them mentalities? Probably not: History has shown that speakers of any language can end up in polarized groups in which each devotes unlimited time and attention to vilifying the other side. On the other hand, English has no obligatory features that might encourage the reporting of truths, as opposed to supposed truths, possible truths, or merely reported as opposed to verified truths. English does not have an inferential mood, like some other languages, which distinguishes between witnessed and merely reported events. And evidentiality is not a grammatical category in English; speakers are not obliged by any grammatical construction to say how they know what they know, as they are in some languages.

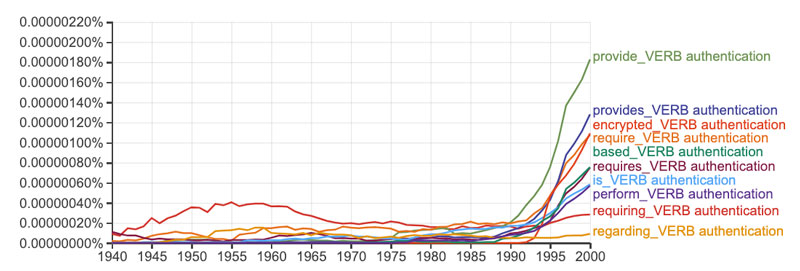

Perhaps as a remedy for this plague of misinformation in English, there are distinct changes in usage around the words we use to evaluate what we see and hear. This graph, for example, shows a broad marked increase in the use of the noun authentication, but an especially sharp increase in the collocations "provide authentication" and "require authentication". Drilling down into the citations on these predicates shows that many of them — as you may suspect — have to do with computation. But many others occur in legal, commercial, and political spheres.

Another sharp explosion in usage came around 1930, when the insertion of reportedly and allegedly before various verbs began a rapid increase.

What would account for this? Were writers formerly less inclined to commit to paper statements that had not yet been verified? Or were they worried about a greater likelihood of being held accountable? There is some evidence suggesting the latter: the phrase "sued for libel" also shows a sharp increase starting around 1930, and it has been steadily rising since.

The fact that our societies remain entrenched in division suggests that the linguistic remedies floated above are in fact not remedies at all, and this is surely not surprising: language alone can't be expected to solve a problem that language itself is partly responsible for. The quote from E. F. Schumacher that I began with might suggest that technology exacerbates our problem, and hardly anyone would dispute this. But again, it does not seem promising to look to technology to solve a problem that technology has magnified. So it behooves us all to maintain a healthy skepticism about information generally. The modern world makes it even more of a challenge to "get real" when we are communicating with language.