Language Lounge

A Monthly Column for Word Lovers

That Only Happens in the Movies

Linguistics and Big Data have been a fruitful partnership since they first found each other, and new hookups with promising results are happening all the time. Early last month Mark Davies of Brigham Young University announced the availability of two new corpora that will undoubtedly provide fodder for many insightful probes. The two new corpora are the TV Corpus, comprising 325 million words occurring in 75,000 TV comedies and dramas from 1950 to 2018, and the Movie Corpus, with 200 million words in 25,000 movies from 1930 to 2018.

The BYU collection of corpora is an invaluable resource widely used in linguistic research, and if you're a regular reader of the VisualThesaurus you will have come across references to COCA (the Corpus of Contemporary American English), COHA (the Corpus of Historical American English), and others before. These two new corpora have me salivating because they provide an opportunity for me to explore further a subject I've looked into before: the peculiar fact that fiction, despite its attempts to suggest that it mirrors life, contains linguistic patterns that do not rise to the level of appreciable frequency in more general samples of language.

An advantage of these two new corpora is that they capture only dialog, not description. Narrative fiction is replete with descriptions of ordinary things that people do. Readers of it, depending on the genre, will encounter an inordinate number of accounts of people playing with their hair, brushing their lips against this or that, taking deep breaths, or doing various other tiresome things that in ordinary discourse do not merit description. These actions are no less common in TV and in the movies, but we see them rather than read about them, so the new corpora should provide the basis for examining whether the way people talk in the movies and on TV is like the way we really talk, or whether it's a peculiar subset of the way we talk.

In his descriptions of the new corpora, Davies notes a research finding: "TV and movie subtitles often agree better with native speaker intuitions about common, informal English than actual spoken corpora." This is undoubtedly so because crafters of screenplays and TV scripts have a bit of time to think about and capture how people talk — or perhaps how people would like to talk — whereas in real-time we are necessarily a bit sloppier than we'd like to be and few of us talk the way we might like to think we talk, or would like to talk: our actual speech is marbled with disfluencies, anacoluthia, fillers, and other deviations from perfection. But aside from that, the content of what we talk about in life is not the content of what people talk about in the movies.

My first instinct regarding the new corpora was to look at the verb win. We all like to win, and many popular movies typically feature someone winning against the odds. For comparison to movie talk, I looked at various corpora of spoken English, drawn from British and American sources. Results of the two searches are informative: certain objects of the verb win are among the top collocations in both movies and in general conversation: game, race, prize, championship, election. A few are more common in general language (award, medal, title), and some are more common in the movies (war, race, chance).

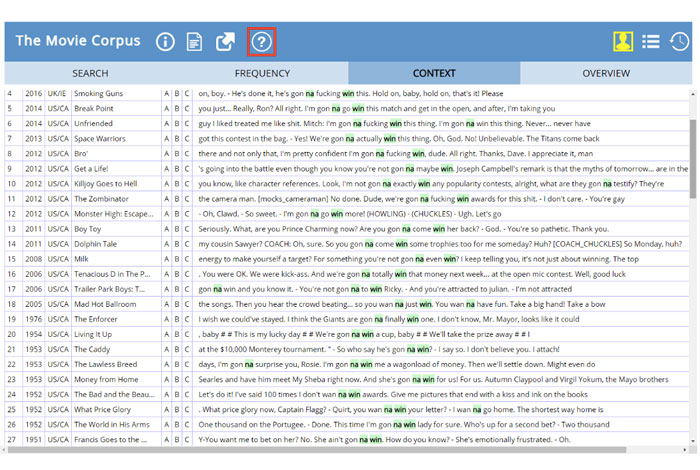

What stands out in movie talk, however, is a particular locution that does in fact rather drip of cliché: "X is (not) gonna win __________." The construction is about five times more common in movies than in general conversation. Here's a sample to give you the general flavor:

It's perhaps notable that insertion of the intensifier f*cking between gonna and win doesn't occur till 1992 but thereafter it takes off like wildfire, appearing in nearly 30 different film scripts. This may be reflective of the fact that this modifier is now bleached to the point that it escapes the censor's frown. Combined with that is perhaps the fact that contemporary movie protagonists are often a lot rougher around the edges than the heroes of old. Clark Gable or Jimmy Stewart would never have uttered such words on screen.

Love is a recurring theme in life and in movies. It should come as no surprise that love as depicted in the movies is a completely different kettle of fish than the love we talk about in ordinary life. Surely if this were not so, there would be much less reason to go to the movies! I looked at words surrounding the word love in the Movie Corpus, and in a corpus of spoken English. The top contenders in the movies: in love, make love, true love, love-making, love forever, love affair, love song, sweet love. In ordinary conversation: love food, love to cook, unconditional love, love watching X, love cats, love affair. The disconnect is perhaps not surprising. Love affair is a frequent enough subject of conversation in movies and in real life to rise to statistical significance, but beyond that, it seems the we ordinary mortals spend more time talking about the love of food and cats than we do talking about romantic love.

Another feature of the new corpora is the facility to examine differences between English dialects in the talk of movies and TV programs, since the data is drawn from scripts of multiple Anglophone countries. This too is instructive in a somewhat predictable way. The words that figure more prominently in British films are not at all surprising — they are nearly all words that we think of as Briticisms: advert, barmy, chuffed, flatmate, guv, knackered, poxy, snog, sodding, and whinge, to name just a few. The words that show up with much more frequency in American film scripts shows a similar pattern of popular Americanisms (burrito, downtown, freeway, hustle, roommate, sassy, senator, and many others) but I was intrigued to see a couple of words in the American list that don't strike me as being particularly American in usage: undefeated and quit. So I looked in the corpus for citations of these. The more frequent use of quit in US screenplays is due to a common meaning that, while present in British English, is historically and currently mainly a North Americanism: to put an end to a state or activity, as in quit smoking/playing/stalling/drinking. As for undefeated: that goes back to winning. The most frequent collocation using this word in movies is undefeated champion, and of the 36 films in which the term is used, only three of them are not American. Now that, surely, is winning!

This is only a small sampling of the riches to be found in these new corpora and I will be exploring them with interest for quite a while, but these initial searches confirm what you may have long suspected was the case: while it may be true that language in movies "agrees better with native speaker intuitions about common, informal English" than actual speech does, it is also true that what people talk about in movies is a world of its own. We are lured into the silver screen by the verisimilitude of the language to what we know, but once we are there, it's quite a different place from the world we live in and talk about.